- Home

- Shauna Holyoak

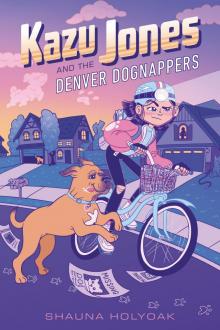

Kazu Jones and the Denver Dognappers

Kazu Jones and the Denver Dognappers Read online

Copyright © 2019 by Shauna Holyoak

Cover illustration © 2019 by Grace Hwang

Designed by Mary Claire Cruz

Cover design by Mary Claire Cruz

All rights reserved. Published by Disney • Hyperion, an imprint of Disney Book Group. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. For information address Disney • Hyperion, 125 West End Avenue, New York, New York 10023.

ISBN 978-1-368-04444-8

Visit www.DisneyBooks.com

To my husband, Mike—

my champion, best friend, and lobster

CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Chapter Thirty-eight

Chapter Thirty-nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-one

Chapter Forty-two

Chapter Forty-three

Chapter Forty-four

Chapter Forty-five

Chapter Forty-six

Chapter Forty-seven

Acknowledgments

About the Author

CHAPTER ONE

Mom let me keep my paper route even though there was a dognapper on the loose. It was a tough sell, but I convinced her I was a ganbariya, with the spunk to slog through the mud pits of life.

Mom was distracted by my clever Japanese skills and didn’t suspect a thing about my detective work. It was always about the detective work.

But even girl detectives with ginormous watchdogs named Genki got nervous about dognappers roaming their town before sunrise. So when I delivered papers, I rode my bike fast and kept my eyes open for suspicious characters.

This morning I stood on the pedals of my baby-blue Schwinn cruiser as I turned the corner at the end of my block, the crunching gravel under my wheels loud in the still streets. Genki ran beside me, nearly as tall as the bike. Dad had trained him to be my slobbery bodyguard, and there was no place I could go that Genki wouldn’t shadow me.

My basket was packed with rolled newspapers, and they caught air each time my bike jumped the curb or hit a rock. Like always, I had pulled my sneakers on without tying them, and the laces wagged in the wind.

At dawn, the fall sky in Denver, Colorado, was the color of purple velvet, and the air smelled like wet dirt and smoke, probably from people using their fireplaces for the first time. No one turned their porch lights on this soon after summer, so the streets were crowded with dark shadows.

I cycled with my head down, pumping so fast my feet nearly spun off the pedals. As I neared the corner house, where a kitchen light glowed like the Bat-Signal, I noticed movement in the back garden. Genki’s head snapped to attention.

I slowed down, and Genki’s gallop turned to a trot as my bike hugged the curb. We both watched as a shadowy figure shuffled around the garden, pausing to hunch over a pile of dirt. I squinted past the squat trees surrounding the yard that looked like soldiers standing guard. I could just barely see the person drag something heavy into a hole, followed by a loud “Oomph!”

I swung my leg over the crossbar. Genki matched my steps and studied my face as I rested the bike gently against the sidewalk. We hid behind a tree.

The suspicious character wore a dark robe and walked like a hunchbacked monster. As if savoring each moment, it began to fill the hole with a miniature shovel. It had to be burying a body, probably one of the dogs that had been snatched by Denver’s Dognapping Ring—nearly fifteen dogs had disappeared over the summer.

Genki leaned into me as I knelt, his whining a low and practically soundless vibration in his chest. Even though he was a big dog—a mastiff—he had a social anxiety disorder. At least, that’s what Mom said.

As I peeked around the tree trunk, my elbow knocked over a metal rooster that decorated the lawn, and it clattered like a tin-can tower tumbling to the ground. The hunchbacked monster’s head snapped up, a halo of hair frizzing in the kitchen light. I jumped and Genki barked.

I darted across the lawn and stood my bike upright before running it alongside me, Genki trotting behind. When I turned onto Colonial Avenue, I let it go. It wobbled a few feet and then crashed in front of my BFF March Winters’s house, the newspapers in my basket exploding onto the road.

Scooping an armful, I ran to March’s window—the last one on the second floor—and began chucking papers. They thudded against the house, missing his window wildly, but his light flicked on anyway. March was always the first to wake up in the Winterses’ house, rising as soon as his alarm went off at six thirty. Show-off.

He strained to open the window and then shook his head when he recognized me. “What are you doing here this early, Kazu?” he whispered.

“You need to call the police,” I whispered back. “Your neighbor is a criminal.”

March rolled his eyes. His springy dark hair was flat on one side from sleeping. “I’m not calling the police.”

“Well, I can’t do it.” I looked over my shoulder for the Hunchbacked Monster but just found Genki plopping down behind me and licking his front paws. “On account of they don’t take my calls anymore.”

“Why should I join that list?”

“Because there’s someone burying a dog over there.” I pointed across the street with a shaky finger.

Suddenly March’s alarm blared, and he disappeared from the window. I crouched on his lawn and began collecting the rolled newspapers around me, watching for the Denver Dognapper as I worked. Genki became interested in my movements and pounced on each paper before I could pick it up.

“Stop it!” I snapped, and Genki finally stopped.

“You saw it?” March reappeared in the golden light of his window frame. “My neighbor, burying a dog?”

I stood with my newspapers. “Probably one of Denver’s Missing.”

He sighed and folded his arms across his chest, tapping his elbow with his pointer finger. “I’ll call. But you stay until the police get here—in case you’re wrong.”

“Do you not know me?” The sun was coming up, and the new light made me brave. I stopped whispering. “When would I skip out on an investigation?”

“Stay right there,” he said. “I’ll unlock the front door.”

I sat on March’s curb while Mom talked to the policeman and Eleanor Fitzman, the old lady who lived kitty-corner from March. Genki lean

ed into me, breathing into my ear and getting slobber on my shoulder.

Mrs. Fitzman bent over her cane while she talked to Officer Perks. She was wearing a navy-blue bathrobe and had Einstein hair. The policeman glared at me from over her head, twice as tall as Mrs. Fitzman, his hair black and curly. He looked like an ordinary guy dressed in a policeman costume.

Mrs. Fitzman held one hand to her neck as she spoke. “Mister Mapples had been with me for fifteen years, which is long for a pug. And that’s five years longer than Hank now,” she said. She looked at Mom, adding, “Mr. Fitzman passed five years ago.”

Mom nodded dramatically, as if her rapt attention made up for my dognapping accusations.

As the old lady explained the slow decline of her now-dead husband, I rested my head on my knees, looking up the street at all the houses still waiting for their newspapers. At the corner house I caught an old guy watching us, his upper body leaning over a garbage can. I craned my neck to get a better look, and he turned around, pulling the garbage can behind him.

Mrs. Fitzman was still talking. “When I awoke this morning—early because of the insomnia—Mister Mapples was gone. I couldn’t bear to sit with his lifeless body one minute more, so I buried him in the flower patch.” We all knew this was true because she had unburied him for us ten minutes ago, and then shuffled inside to locate the doggie adoption certificate and a framed photograph as proof that Mister Mapples was indeed her dead dog.

Officer Perks looked like he was competing in the Most Bored Person on the Planet Contest. He pretended to take notes. Mom cinched her cotton robe tighter, stole a glance my way, and narrowed her eyes at me, deepening the crease between her brows.

“I’m so sorry Kazuko disturbed you this morning,” Mom said, motioning me over. Even though she had left the house in a hurry, her black hair was slick and perfectly straight.

I stood and walked toward them, shoving my hands deep into my jacket pockets. Genki followed, hanging his head like he knew we were in trouble.

“I’m sorry,” I said.

“Oh, sweetie,” Mrs. Fitzman said. She reached out and grabbed my hand. Her palm was soft and fleshy, and the dirt smiling beneath her fingernails made me like her. “You performed your civic duty. With all the dogs disappearing, you had every reason to be suspicious. Right, Officer Perks?”

Officer Perks hesitated before responding. “Kazuko is known for her passionate pursuit of truth and justice.”

Mom nodded as Officer Perks repeated, “Well known.”

“Then,” Mrs. Fitzman said, tapping her cane to each word, “good for you.”

I smiled, but stopped when Mom’s face hardened, her jawline suddenly pointy and dangerous.

“Kazuko will be late for school if we don’t hurry. And I still have to finish her route,” Mom said, squeezing my hand knuckle-tight as she did. She wasn’t happy about doing my job when she still had her own to do. She was designing a new exhibit for the Denver Exploration Museum for Kids. “My apologies, Officer Perks. And, Mrs. Fitzman, I’m sorry for your loss.”

The policeman stepped forward and grabbed my elbow to stop me. “Your dog is off its leash.” With all the dognappings, the city had gotten pretty strict about leash laws.

I shrugged. “He’s really good about following me.”

Officer Perks scratched something down on his pad and then ripped it off with flair. I took it from him and read, Loose dog warning. Next time, maximum penalty. Signed, Officer Warren Perks. I folded the paper into a tiny square and shoved it into my pocket, pinching my lips together so I wouldn’t say anything.

Mom and I walked to the car, which was parked in front of the Winterses’ house. To all the neighbors peeking from behind their curtains, it probably looked like a loving mother was guiding her daughter to the car with a gentle hand pressed to her back. But actually, Mom’s fingers drilled into my spine, and under her breath she rattled off stinging threats about extra chores and reduced screen times that continued as we drove down the street.

Genki lay across my lap, his whining echoing inside the car. “It’s okay, pup pup.” I scratched his ears to make the social anxiety go away.

“This troublemaking binge has got to stop, Kazuko Jones.” Mom drummed her fingers on the steering wheel. “What happened to my sweet girl who was all about crafts and swimming lessons and lunch dates with Mom?”

“I’m nearly eleven and one-quarter,” I said, unable to stop myself. “Not seven.”

Mom’s lecture continued as we turned onto Summer Glen, and I distracted myself by studying the house where I had seen the old man earlier. It was one of my houses, and the spookiest one on my route. Dark brown and barely visible from the road, it was shrouded by fir trees and gave me the creeps. And as we passed, I could have sworn I saw someone peeking at us through the blinds in the corner window.

CHAPTER TWO

“I’m grounded from you again,” March said as I slid next to him on the bus. We always sat on the last bench by the emergency exit, where no one bugged us because we were fifth graders.

“How long this time?” I pulled my Sleuth Chronicle from my backpack. I was just thirty dollars short from getting my own iPad, which I would use to digitize my detective business. The Sleuth Chronicle was almost full, and no self-respecting detective ran their business on paper these days.

Mine was the second-to-last stop, and the bus was almost full. It echoed with chatter and laughter and smelled like moldy oranges.

“Now through the weekend.” March rolled his eyes before facing the front of the bus. He was tall and skinny with crazy wide eyes. Somehow he had gotten the flat side of his hair to fluff up since I saw him earlier that morning.

I shrugged. “I’m grounded for a full week—we couldn’t hang out anyway.”

March turned to me again, his eyebrows pulling together. “You’ve got to stop being so nosy about the dognapping ring.”

I tapped my pen on the open notebook. “Impossible! I’m meant to solve crime.” Like studying for a test, detecting felt like the logical thing to do. Mom called that feeling atarimae. If you saw an old lady struggling to bring in her groceries, then you helped her bring in her groceries: atarimae. If you made a ginormous mess creating a papier-mâché weremonkey, you cleaned it all up—even the newspaper globs that somehow lodged beneath the tabletop, hardened like cement, and made your dad swear when he found them: atarimae.

And if dogs in your town were disappearing and you knew you could find the dognapper, you solved the crime and saved the day: atarimae.

I guessed that Mom felt the same way about curating exhibitions, and Dad felt the same way about engineering.

“You’re a kid, Kazu. Kids don’t solve crime.”

“Willie Johnson was just twelve when he won the Medal of Honor during the Civil War,” I said. “Joan of Arc was thirteen when she led the French army to victory. And David was fourteen when he killed Goliath.” I opened my notebook. “The only thing holding us back from saving the planet is right up here.” I tapped my temple with the pen. “And grown-ups—they’re kind of a bummer, too.”

He leaned into me, looking over my shoulder at the Sleuth Chronicle. It was an aquamarine leather-bound journal where I recorded all the objective facts, deductions, and clues on current cases. I flipped past the Fourth-Grade Lunch-Box Thief, the Raffle-Ticket Conspiracy, and the PE Teacher Shapeshifter Rumor to land on Denver Dognappings.

I stopped on a page labeled Suspects, wrote down Mrs. Fitzman’s name, and then crossed her out, since she had been both suspected and cleared that same morning.

Also crossed out: Eugene the garbage collector, March’s fourth-grade teacher, Mr. Hildebrandt, and the animal control lady who took Genki thirteen months ago when he jumped the fence to chase a couple of squirrels who had it out for him. He’s a sucker for squirrels.

I snapped the notebook shut and wrapped it with a red rubber band from the paper route. Folded newspaper articles about Denver’s Dognapping Ring were stuffed inside

and ruffled beneath the band.

“I can’t believe your mom’s still letting you do the paper route by yourself.”

“With Genki, she never cared before. But after this morning, she might start driving me again. And not to protect us from the dognapper, but to protect the neighborhood from me.” Disappointing Mom seemed to be another of my natural reflexes.

March nodded, hugging a thick binder to his chest. I was sure all of his homework was neat and complete inside. “It’s picture day today.” He cocked his head, examining me. “Are you ready?”

I smoothed my hair with flat palms. In all the commotion of the morning, Mom must have forgotten. I looked at my jeans, the knees split wide, and my oversize gray T-shirt with a stain on the chest. “Um…My sentence may be longer than one week once this outfit is documented.”

March shook his head and sighed. Then he held out his hand, an invitation to a thumb war, and we finger-wrestled the rest of the drive to school, March winning every time. That kid had freakishly strong thumbs.

Mrs. Hewitt bounced on her heels behind the music stand as she told us the story of Oliver!, her all-time favorite musical. The first song she wanted us to learn was called “Food, Glorious Food.” Apparently, it was about a bunch of starving orphans who had a hankering for sausage-based dishes.

Mrs. Hewitt was suspiciously enthusiastic about this year’s Thanksgiving concert, insisting we prepare early so that we could be Broadway-ready. She paced like a solider in front of the room, reciting the lyrics. But as she got more into it, she began to sing, her white hair bobbing to the beat. She belted out the ending, and some of the girls covered their ears as she shrieked, “FOOD, glorious food, glorious foooooooooooood!”

Silence filled the room for a moment before cackling erupted from pockets in the choral risers. Madeleine Brown, the only other Asian girl in the fifth grade, led a group in giggling fits followed by whispering and then more giggling.

Madeleine was a whole head taller than me and her hair was long and wavy, while mine was straight, barely dipping below my shoulders. She was a soccer star who always wore athletic gear to school, including, sometimes, cleats. Today she had on a team hoodie and running capris. Even without spiked shoes, kids avoided her in the hallways; getting elbowed by Madeleine Brown could take you out for an entire recess.

Kazu Jones and the Denver Dognappers

Kazu Jones and the Denver Dognappers